:1:

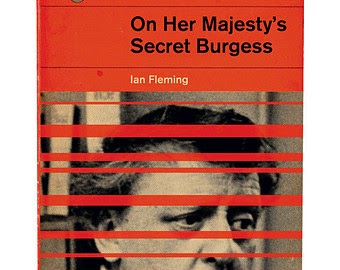

The Worm and the Ring had a problematic publication history. Burgess based it in part on his time teaching in Banbury Grammar School (now Banbury Academy) in the early 1950s, a provenance that caused difficulties. Wikipedia is to the point:

The novel was withdrawn from circulation following a libel action by Gwendoline Bustin, the secretary of Banbury Grammar School, where Burgess had taught in the early 1950s. Several characters were recognisable as figures from the school, but only Miss Bustin, later Lady Mayoress of Banbury, objected. Heinemann agreed to 'amend all unsold copies of the book' (The Times, 25 October 1962) but actually pulped them. A revised edition of the novel, with the libellous elements removed, was published in 1970.It is this revised edition that I read (in blue, at the top there; I have never seen a copy of the first edition from 1961), and I confess myself intrigued as to how much it has been altered. The school secretary character, Alice, is portrayed as a shallow, neurotic spinster, a gossipy pest with a desperate crush on the (married) headmaster, Woolton, that she sublimates by alternately coming round to his house to cook for him whilst his wife is ill in hospital, but also spreading rumours about Woolton's supposed sexual turpitude with his female teachers and even with schoolgirls. The town doctor, Leary, discusses her near the end with teacher Charles Howarth, one of the book's main characters. 'What seems to be the matter with her?' Howarth wonders, and Leary replies:

'Frustration. Hypochondria. Hysteria. One of these days she may be really dangerous. Sex does queer things to people, especially when it's leaving them. It rends them like a departing devil. I've seen her type before. The bitter spinsters, the dried-up duennas who advance and retreat at the same time, lure a man on then call the police.' [263-64]Blimey: if that's how the character was after the potentially libellous descriptions of Ms Buston were removed, I shudder to think how the original version painted her.

Woolton is not really groping his female staff and having sex with the girl students, but that doesn’t stop the gossip. In fact Woolton is an aging, rather ineffectual classicist, a woolly-liberal sort of Wotan; his wife Frederica has mental health issues and his elderly mother, who lives with them, is going senile. He is optimistic about the future, though. Indeed, optimism about the future is his defining characteristic. He is overseeing his school’s move from the tumbling-down old Victorian building to a bright new glass-and-steel 1951 structure out of town. ‘Space, light, air,’ he tells his wife. ‘Shining laboratories, rational chairs and tables. But above all space. We’ve been working in incestuous rat-holes.’ [25] It turns out that the new building is not all it’s cracked up to be, built as it has been by corner-cutting contractors who got the job via bribes. But Burgess’s point is more central: Woolton is foolish to think that putting children in bright new surroundings will overwrite the Old Adam inside them. Indeed, one of the things that is particularly good about this novel is the way it portrays the life of the kids themselves: the pack-dynamic, the aimless bullying and teasing, the anxieties and pettiness and boredom. Original sin, Burgess thinks.

The novel includes several child characters, but the main emphasis is on the adults. We get the music teacher Ennis, presumably the same character as the protagonist of A Vision of Battlements six years on; and the absent-minded master Mr Lodge. More substantially we get Charles Howarth the modern languages teacher, a Catholic trapped in a sexless marriage with his over-devout wife Veronica: the birth of their only child, Peter, produced life-threatening bleeds; a second child would probably kill her, and with contraception off the table for a 1951 Catholic celibacy is her only option. This, of course, does not make Howarth happy, and he plans an affair with another teacher, Hilda Connor, herself married to a Major in the army who is often away. Finally there is the plausible, wealthy but morally empty Gardner, who has earned himself a doctorate by plagiarising the oddly complaisant Howarth’s scholarship, and who spends the novel plotting to unseat Woolton and claim the headship for himself.

The book is in four parts because Wagner’s Ring Cycle is disposed into four opere. The parallels between the two involve various modes of slippage, and it is to Burgess’s credit, I think, that The Worm and the Ring reads more-or-less smoothly as a well-written and well-observed novel in the realist mode about the travails of being Catholic in 1950s Britain. Still, the parallels are there, and it would be a pity not to notate them a little.

Wagner’s cycle is, in part, about the Gods (Burgess’s teachers) moving into a splendid new palace, Valhalla (the new school building). This has been built by the giants (the parish council in Burgess’s novels: old farts and crusty noblemen), but must be paid for.

Burgess's ring is a schoolgirl’s diary, stolen at the opening of the novel by the ugliest boy in school Albert Rich (that is, by Alberich). In amongst all the usual trivia of a teenage day-to-day, this diary includes an account of the girl in question (Linda; but she is one of Burgess’s interchangeable Rhinemaiden schoolgirls, of whom there are several) in the headmaster’s office being pressured into the performance of lewd acts. A schoolmaster confiscates the diary from Albert Rich, and the incriminating document ends up in the hands of the unscrupulous Gardner. He interviews Linda, and discovers that the incriminating passages reflect no reality, but constitute a sort of written-down daydream of erotic possibility. But he browbeats the girl into ‘confessing’ that the sexual transgression actually took place. Then he lays his plots to use this information to discredit and unseat Woolton. That is to say, the metaphorical 'ring' gives the possessor power (within a limited ambit: the power to focus community outrage and unseat a sitting headmaster) but at the cost of 'giving up' love, or more tenuously, turning one's back on sex as a positive.

The character who gets most narrative attention is Howarth, and his Catholic angst is close to what the novel is 'about' in a larger sense. He pursues Mrs Connor, and has almost persuaded her into bed with him when he experiences a change of heart and promises to himself to go back to confession, and mass, and the straight-and-narrow. But Providence conspires against him. He agrees to take 25 schoolchildren on a school trip to Paris. Since some of the kids are girls he knows that there must be a woman to chaperone them, and he arranges to have his wife accompany him. This was his plan: for the two of them to have a holiday which they could not otherwise afford, and rekindle some of the romance in their marriage. But only days before the trip Veronica haemorrhages badly and has to be hospitalised for a hysterectomy; Woolton, without consulting Howarth, gets Hilda to accompany him in Veronica’s place. Alone in the world's most romantic city with the woman he has desired so long, Howarth’s new principles desert him and the two have sex.

Whilst reading I wondered whether Howarth is the novel’s Siegmund, and his son Peter (whose teenage wrestlings with his over-developed religious yearnings are given a lot of space) Siegfried. But of course a moment's thought shows that Howarth is supposed to be Siegfried (Hilda, clearly, is Brünnhilde), and Peter presumably an achronological or inverted-generational version of Siegmund. The child is father to the man, according to some, after all. The boy prays for martyrdom as a way of circumventing the many temptations with which he is afflicted, and almost gets his wish when he is bullied onto the (new) school roof to fetch a lost cricket ball. He takes the bullying as sectarian persecution (‘“You’re making me do it,” said Peter, “Is that it?” “Yes that’s right,” said Rich. “We’re making you doing it.” “Because I’m a Catholic? Because you think Catholics are scared?” “Yes, you are scared. The lot of you.”’ [235]). When the shoddily built drainpipe breaks, Peter falls down and is impaled on railings. But he goes down in beatific mood: ‘A bird twittered on a branch of the elm. A good act of contrition didn’t matter now; he was safe’ [238].

In fact Peter does not die, though he is badly hurt; and the shock of this, combined with Hilda’s news that her husband is to be posted to Gibraltar and she with him, reconciles Howarth to his wife. (Burgess's account of the novel in Little Wilson and Big God suggests that Peter does indeed die in the first edition; if so, the revision was a canny one. It works better more obliquely framed). The Howarths leave en famille for Italy, where Charles will work for an American (an old wartime buddy) who has offered the polylingual teacher a job on his vineyard. As for Woolton, he is dragged before the parish council and accused of various delinquencies on the strength of rumour only (Howarth had previously found the incriminating diary in Gardner’s drawer and burnt it). Woolton vows to fight any calls for him to stand down; but then his mother dies leaving him a very large sum of money in her will, and he—plus his wife, newly cured of insanity in rather deus-ex-machina style—leave to start their own school. Gardner gets to be Head, and the novel’s closing paragraphs paint his accession as the culmination of the book’s Götterdämmerung.

Gardner was not concerned to ask whether the coming regime was based on a defensible premise. Good and bad, he recognised, were terms to which he could attach no ethical significance. An action was justifiable if it led to the possession of the thing it was desirable to have. Happiness was neither here nor there: what counted in life was the fulfilment of one’s own peculiar daemon, the realisation of a pattern which existed outside the caprices of appetite, ambition, desire. The man born to rule was neither the good man nor the bad, but the man capable of existing as a sheer function, a sheer personification of order. Woolton had been destined to find some kind of content in the irresponsible dreams of a Roman or Hellenistic Utopia, for—despite his liberalism—Woolton was fundamentally irresponsible. Howarth was another who would succeed at nothing. He had a brilliant linguistic quirk coupled to a weakness of character that would, till his penurious end, lead him from bed to bar to bed to confession, over and over again. They both had their destined ways; let them fare forward or backward. Upward lay Gardner’s way. [272]In terms of the book’s quasi-realist bona fides, Burgess links this to the (as he saw it, disastrous) elimination of grammar schools and levelling of all education to the spurious democracy of the secondary moderns. ‘Democracy,’ Gardner tells his teachers, ‘cannot be reconciled with the notion of an élite’ [268]. Ennis, one of Burgess’s several mouthpieces (though he is a very minor character in The Worm and the Ring) retorts ‘you’ve got to have an élite' or ‘everything will be diluted … we sink to the lowest level. We will water the wine until there is no wine left’ [268]. I like that Burgess elects to use the fancy-French spelling of ‘elite’ here, a sort of meta-elitism of terminology. And one need not agree with this perennial Burgessian crotchet for the novel to work. That said, it probably is true that this summing-up at the end, from Gardner’s more-or-less sociopathic perspective, works better as an attempt at mythic interrogation of the logic of Wagner’s cycle than a meaningful critique of anti-elitism in pedagogic practice.

:2:

Why the Wagner, then? Just for the LOLs of undertaking a large-scale Ulysses-style everyday-novel-pinned-to-grand-mythic-story exercise? Geoffrey Aggeler thinks that the ‘discrepancy here between subject matter and heroic musical form suggests that the book is to be viewed as burlesque’ [Geoffrey Aggeler, Anthony Burgess: the Artist as Novelist (University of Alabama Press, 1979), 209]. I’m not so sure. After all, you wouldn’t call Ulysses a burlesque, although the disparity between that novel’s various Dublin lowlifes, wankers and boozers and the Homeric half-divine heroes which they embody is, if anything, more pronounced than is the case in The Worm and the Ring. And burlesque doesn’t seem to me to describe the effect of this novel: sometimes funny but often deeply engaged in precise social and environmental description, thoughtful, even deep.

Put it another way: Burgess’s novel is about the experience of being a (lapsed Catholic) teacher in a provincial secondary school in 1951; and therefore—on a personal level—it is about guilt, sexual desire and growth, and—in a larger sense—about education, both professionally and spiritually considered. What is Wagner’s Ring about? Well, at the risk of sounding flippant, it’s about lots of things: but centrally it’s about power, as temptation and curse; and about love; and about the roots of a particular cultural, national and (notoriously) racial identity, this latter being curiously woven in with a cosmic pessimism that celebrates the raw force of human heroism even as it acknowledges that such heroism is always doomed.

It’s not, perhaps, immediately obviously how these two magisteria map onto one another. Wagner's Ring is many things, but it is not Catholic, not about guilt, is wholly uninterested in issues of atonement and encompasses no redemption. Nor, really, is it about ‘education’, broad though that latter term can be. It’s strange to note this, really, since the list of things the Ring has been taken as being about is impressively varied. Hitler, famously, thought it was about the triumph of the racially pure German people: ‘I was filled with proud joy,’ he told Wagner’s daughter, ‘when I heard of the victory of the Volk—above all in the city where the sword of ideas with which we are fighting today was first forged by the Master.’ [quoted in John Deathridge's excellent Wagner: Beyond Good and Evil (Univ. of California Press 2008), 63]. George Bernard Shaw on the other hand thought the whole cycle an allegory of the evils of capitalism: this is his essay ‘The Perfect Wagnerite’ a Shavian-Marxist exercise in explicating the wicked effect the Rheingold has on the world (he has a rather splendid theory that the Tarnhelm is a Victorian factory-owner’s top hat). It is the river with which the cycle starts, during that still-extraordinary and superb vorspiel to Das Rheingold where the E flat drone and the spacious variations of the E flat chord build for seven minutes to indicate the flow of the water. Out of the river the whole drama comes and into it everybody disappears at the end. The river is time, or change, or life, or whatever you fancy. But Burgess chooses not to take the river’s gold as anything so literal-minded as actual gold. Money plays only a minor role in The Worm and the Ring. The novel is clearly ‘about’ power, but in a strangely limited, even strangulated manner. Gardner is surely too big a villain, too Machiavellian and driven, really to be content with a position of authority so milksop as headmaster of a provincial secondary modern school. Indeed this, rather than the mismatch between Wagnerian majesty and pettifogging Banbury day-to-day, strikes me as the main disjunction the novel articulates. The question, which I’m still revolving in my brain, is whether it is a deliberate one or not. I would say that this novel does not do (and possibly does not set out to do) what, to pick a rather incongruous comparator, J K Rowling does in her Harry Potter novels: that is, to treat school as a type for the larger world as a whole.

Perhaps the question ought to be: why school, then? I should make it clear that I consider this novel a major piece of Burgessiana; finely written, detailed, memorable. But there is an opacity about the rationale for its backing-up of ordinary life with Wagnerian myth, and a fuzziness, or muddiness, about the way its treatment of guilt and passivity resonate more generally. What is going on?

Another way of framing the issue of supposed disjunction between (say) Gardner's grand ambition and his petty goal (becoming a provincial headmaster) would be to suggest that Wagner's cycle is, fundamentally, about strength; where Burgess's novelistic fascination, here and in his other writing, is with weakness. Weakness is constitutive of humanity, he thinks; and it is precisely the fallibilities of ordinary individuals that ground their interest and specialness for him. Wagner didn't think like that. Of Siegfried, and perhaps conscious that as represented in these operas the character comes over as a violent, impulsive psychopath, Wagner said:

Siegfried should not create the impression of a character drawn with the conscious intention of violating the standards of civilized society; everything he says and does—even the rather cruder aspects of his genuine boyishness—must be presented as the natural expression of an essentially heroic personality who has not yet found an object in life worthy of his superabundant strength. [quoted in Deathridge, 62-3]Superabundant strength is Wagner's Ring in a nutshell: the music is superabundant and strong; the drama is painted in forceful, muscular strokes; strength is beautified and valorised. But there's a wrinkle, the closest Wagner approaches to irony, and it inheres in the paradox of the ring itself. It is the talisman of absolute strength, the short-cut to world-spanning power; but only to the wearer who gives up love (which is to say, sex). Siegfried's superabundant strength manifests in part in his absolute lack of fearlessness; the first he knows of fear is when he lays eyes on the beautiful Brünnhilde, his first sight of woman, and falls in love. Love and fear are, Wagner is telling us, the same.

Burgess's Howarth is all weakness; which, in this context, is to say: all sex and love. He can't, for example, seem to separate out these two terms: eager to shag Hilda, he makes very free with the l-word: 'I do love you,' he blurts, whilst the two are in the school dinner hall one lunchtime. She rebukes him, tries to distract him ('look, those children are making a dickens of a row. We must go and stop them') but he insists: 'I love you. To hell with the children. I love you.' She then suggests running away, and Howarth feels 'a conventional twinge of fear that perhaps his avowals were being taken too seriously'. He presses on: 'I love you. If you were free I'd marry you', to which she rightly retorts: 'nice and safe behind your Catholic marriage' [116-17]. He doesn't really love her, of course; he is just sex starved and desperate. But above all he is weak, with all the usual masculine weaknesses.

This is the titular double-entendre that Burgess, not very subtly, extracts from his Wagnerian source. The Worm is Fafnir, the dragon (there is a pub in the village where much of the action takes places called 'The Dragon'), but it is also the male member, the willy of the Wilson-proxy Howarth. The ring is the vagina. The foci of Howarth's guilt are his lapsed state as a Catholic and his unruly sexual urges; but the novel is very much more about the latter than the former. Sex turns men into possessive and obsessive Fafnir-types; and sex education is an important learning process (not on the curriculum of this 1951 school of course). As the banality of 1951 provincial life is superposed over the grandeur of Wagnerian myth, so sex gets layered over love. Or so the novel implies.

One thing that strikes me as a little odd, in a novel set so centrally in and written so largely about education, is that The Worm and the Ring doesn't articulate any particularly coherent sense of what Burgess thinks education is for. It's not, it seems, about vocationally training tomorrow's chemists, engineers and woodworkers; but then neither (Burgess implies) is it about the disinterested development of the soul, for Woolton's love for the Classics is gently mocked as a kind of abdication. What then?

More, there seem, at least to me, a couple of false steps in the description of the school. Late in the novel we discover that Howarth had been a Captain in the war. I think such a person would have maintained their titular rank in their teaching career, and insisted on being addressed as such (there's a lot made of the status uptick Gardner gets from getting to be called 'Doctor' instead of 'Mister' [note: I'm wrong here, and am corrected in the comments, below]). I was at school in the 1970s and early 1980s, and one of our maths teachers was an old Colonel called Haddon whom everybody addressed as Colonel Haddon. The 1970s were not the 1950s, I appreciate; although my personal experience of school gave the novel particular resonance for me. My old school was also a State grammar that had been moved from poky and tumbledown old buildings in the city centre out to a large 1950s structure of glass and steel. Some of the teachers (they were mostly men, although a few women were on staff) had grown up and been trained post-war; but others were older and had fought in the war, and my main memory of them is that they were, by and large, prone to bouts of what you might call casual violence. There was no cane at my (State, remember) school, but the survivors of the war thought little of knocking kids, hauling them about, throwing board rubbers—hefty wooden items with pressed felt on one side—at them and the like. I got a board rubber in the face in a Physics lesson once, for mucking about, and I still have the small crescent scar on my nose near the bridge. Back in the day it bled a lot, although none of the adults, staff or parents, were outraged by this. It was just how things were. You wouldn't get treatment of the students by the staff like that in a 21st-century school, and that's clearly a good thing; but when I look back what I think is that these were men damaged in subtle ways by their wartime experiences. They survived a long-drawn out and violent conflict; they lost friends; and most of all they internalised a kind of casualization of attitudes to violence. When that generation passed, those attitudes passed with them. The younger teachers didn't treat us that way.

Burgess was of that generation. I've no idea if he was a casually violent teacher; certainly it's not a feature of teaching that figures in The Worm and the Ring. Indeed, although various characters express varying degrees of concern about the welfare of their charges in a general sense, we see little actual teaching. The one exception is where Howarth hijacks his own German class to praise Luther, in order to needle his very Catholic wife (his son is in the class, and Howarth knows the lesson will get back to her). The teachers are less interested in teaching and more in other things: power and sex, especially.

But maybe that's what Burgess is saying about education: that we would do better learning more about power and sex and less about chemistry and the Classics. My old English teacher used to say 'education, from educere, is a drawing out, not a putting in'. He meant that school ought not to be a Hard Times/M'Choakumchild cramming of facts into childish heads, which is surely right. But, looking at that phrase now, it strikes me that there's a pulsing, quasi-sexual motion implied in that putting-in and drawing-out dynamic. The Worm and the Ring is about education in this sense, I'd say: a kind of photographic negative of Wagner's Ring, in several senses, and mostly in that Wagner thinks sex is the secret ruin of strength, where Burgess thinks strength the blankness of an inhuman, abstract force dedicated to the watering down the wine of fallible human sex, joy and life.

One point of correction: my friend Andrew McKie notes "it is (or was) an Army convention that only ranks above Captain are retained in civilian life. A naval Captain would be equivalent to an Army Colonel."

ReplyDelete